“Welcome to Jaffa” brings together works by three artists who have been living and working in Jaffa for decades.

All working in sculpture, Uri Eliaz, Sophie Jungreis and Nachum Inbar recreate spirit out of matter, breathing life into statues made of wood and stone. With solid materials as their starting point, they create images that respond to matter, exploring and working with it to eventually bring out its true essence and story.

It was following Artport’s recent relocation some months ago that we have gotten to know these artists. The move into our new location, on Ha’amal Street, came with enthusiasm at this new neighborhood. After five years of activity on Ben Zvi Road, on premises that were relatively cut off, we found ourselves at the very heart of the local art scene. Together with our proximity to the many contemporary art galleries and artist studios that have flourished in the area in the past decade, we were happy to discover senior artists who have been working in South Tel Aviv and Jaffa for decades.

The exhibition was born in Eilat Street, behind blue iron doors that enclosed a treasure trove of hundreds of sculptures made of wood. The excitement at discovering these dust-covered sculptures had led us to a journey through Jaffa’s narrow alleyways, into rooms and backyards crammed with sculptures, on to sketchbooks replete with drawing, the sounds of hammers hitting the marble and an art-making that never stops.

“Welcome to Jaffa” presents just several of these artists we met on our way, three who have dedicated whole careers to an art that hasn’t always found its way to Tel Aviv’s museums and galleries; artists who have been working in Jaffa for decades, taking note as the art world grew increasingly distant, having moved in other directions.

As a residency program that targets young and mid-career artists, we are excited to welcome in artists who, of an older generation, have long been based in Jaffa and South Tel Aviv – long before we came along.

Uri Eliaz (1931, Tel Aviv) presents over 60 wooden sculptures made of scraps and residue he has been collecting on the beach in Jaffa since the 1970s.

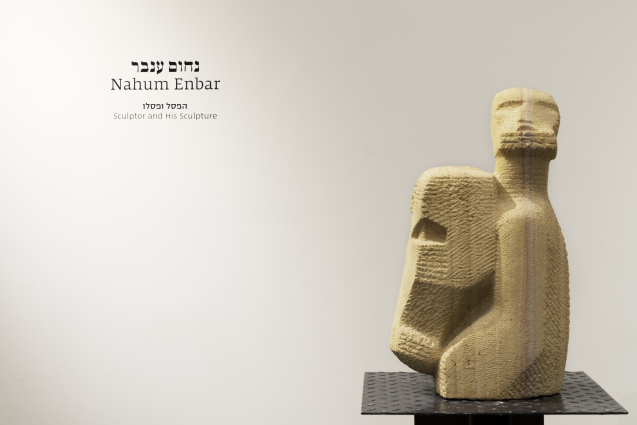

Nachum Inbar (1940, Ramat Yohanan) presents “The Sculptor and His Sculpture”, a series of stone sculptures chiseled directly in stone, by hand, together with drawings that accompany the series.

Sophie Jungreis (displaced persons camp, Austria, after WWII) presents softly-shaped sculptures made in stone, abundant in curves, body parts and unexpected superimpositions.

Read more