Two clay hammers lie supine, resting after banging; a hand-rolled cigarette between one’s fingers, while the other’s foot is extended like a dog’s soft paw. The two have finished erecting the exhibition, and are now lying exhausted on a plain bench installed in the space. One bang was replaced by another; libido was transformed into a work of art. One cannot avoid identifying the pair of hammers—long, slim, and feminine—as self-portraits of Naama Arad and Tchelet Ram, two sculptors with idiosyncratic practices, who have come together in one space of joint creation in this exhibition.

a-part

Each of them individually has been incessantly working and exhibiting over the last decade, boasting a unique, independent oeuvre. Their works are ostensibly different, but they are founded on a similar sculptural principle of accumulating and assembling.

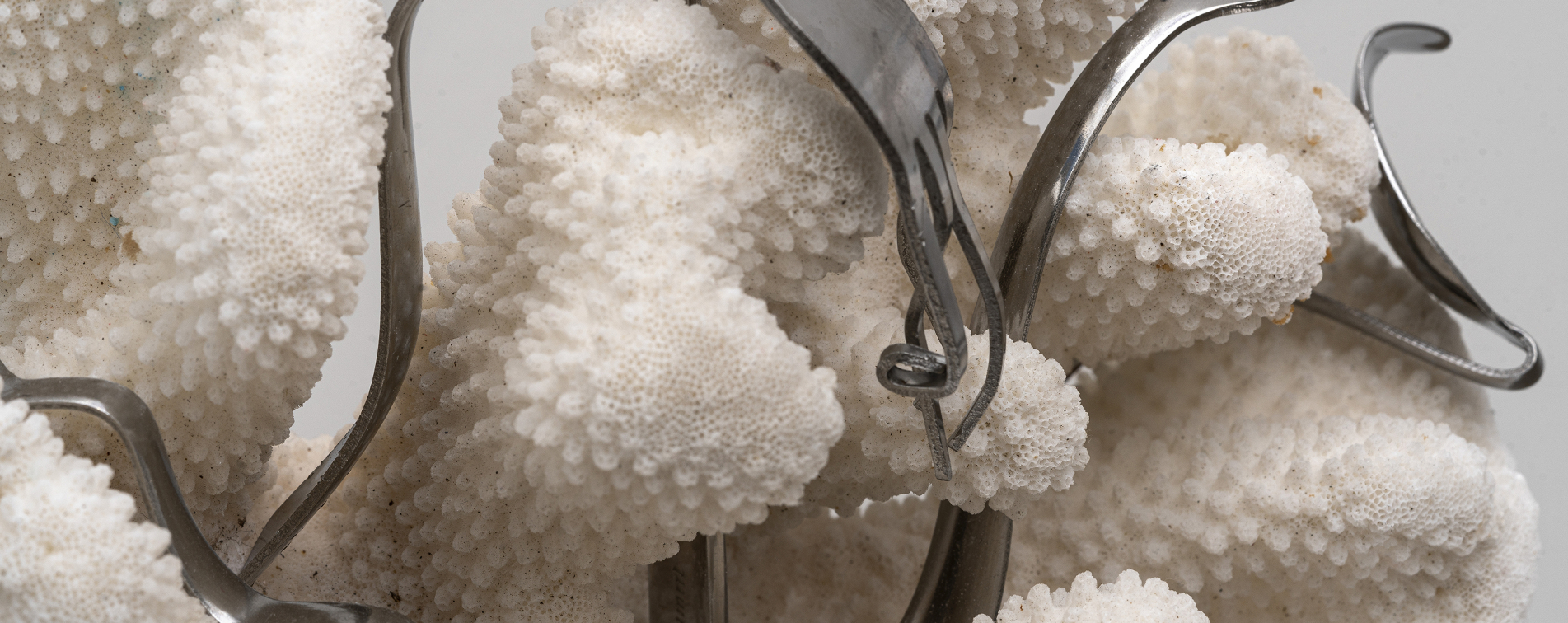

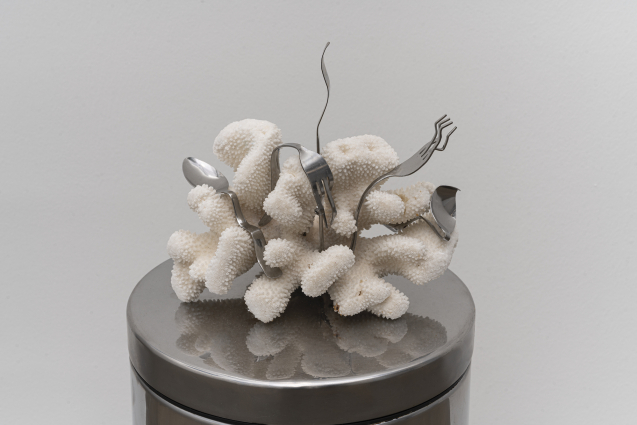

Arad collects her objects by purchasing them from Home Center stores. The objects she culls in these domestic supply and home décor shops are thus “pre” use objects, yet untouched and without a history. Their foreignness stems not only from their newness, but also, mainly, from being commodities manufactured for a consumerist culture devoid of a past and nostalgia, hence objects designed as functions with inexpensive, generic features. In her previous works, Arad used them to create hybrid objects, which she charged with aggressive, alienated libido. Her sculptural work spawned fragmentary, violent forms, floating in estranged environments, ostensibly rendered in a virtual space.

Ram collects objects from the opposite pole. Her sculptures are comprised of discarded household furniture and objects, left on the curb once they became useless. Most often these are objects manufactured between the 1950s and the 1970s, which therefore encode a quintessentially Late Modernist social order. Ram’s collected objects are stained, deconstructed, and their bodies are injured, but they attest to a real life. Her compassionate, poetic touch produces improvised, makeshift shelters from these remnants, structures which always carry a deep yearning for a lost whole alongside a profound sense of freedom.

part of me

Every artist knows those moments in which inspiration reveals itself. This moment is at the core of any artistic action. For this intimate fusion between the artist and the sublime to be made possible in the case of a joint work, there must have existed an overlapping inner space of desire between Ram and Arad.

It is at this point of overlap that they placed their joint studio, bringing thereto the objects they have culled from both sides of time. The exhibition brings together Arad’s “pre” use organs and Ram’s “post” use organs, which are fused into a present through their collaborative work.

ap(p)ar(a)t(us)

The exhibition “A Part from Me” is an installation that outlines the real architecture of an apartment, with a hallway and a parking place. At the same time, inside the spaces, it is experienced as an exhibition of autonomous sculptures.

It is an apparatus that contains a medium-related contradiction: sculpture is an inward “from me” practice—the sculpture is an autonomous body contained within itself, while an installation is an outward “apart” practice—it subordinates all the objects contained in it to a structured set of relationships.

The dual medium strategy reconciles two ostensibly contradictory points of view, thus encapsulating the question around which the exhibition was formed: the ability to contain the self as autonomous and the self as a relationship, as a state which is holistic rather than dualistic.

part-ners

A key cupboard of the type that can be found at the entrance to industrial buildings hangs in the hallway. It contains numerous key hangers, but only keychains are now left, made of sandstone pebbles collected on the beach. It is a group portrait that has been emptied of its subjects; a cupboard of past glory alluding to a relationship with a turbulent, beautiful, and worn out oceanic exterior.

As opposed to Marcel Duchamp’s Bachelor Machine (La Machine Célibataire) created about a century ago, in today’s reality the gravitational force exerted on female singleness is not the bourgeois marriage and procreation dictate, but a social imperative for solipsistic self-realization. For the artists’ contemporaries, it is not repression that threatens the psychological structure, but rather excessive self-awareness. After one hundred years of psychological discourse, we enter the “a part from me” relationship, as we enter the exhibition itself, from the back door, and once again we have no keys.

apart-ment

The continued journey in the exhibition leads the viewer to a bachelorette pad. It is an ascetic apartment for a single female tenant in which contemporary Home-Center items and readymades from previous decades fuse to form sculptural objects. This blend may be construed as a fusion between Arad’s and Ram’s sculptural languages, but it can also be regarded as an inter-generational collage whereby Arad and Ram review their own singleness through the temporal stratum in which their parents were single. The question of coupling becomes a sociological and psychological issue: What was I before my parents were born? What in my present experience was planted as a seed even before my parents became parents?

A pair of artificial eyelashes floats in a plastic tub filled with water, sunken in a bed. This is neither a single bed nor a double bed, but a three-quarters bed, the size of bed conceived for the intermediate phase between maturity and matrimony. The pair of eyelashes, reminiscent of closed eyes, floats asleep inside the tub, which resembles a dreaming head, but also a pregnant belly. The dream and the fetus are both inner places where past and future, potential and realization, longings and fears fuse.

How does one position oneself on an axis ostensibly teeming with prohibitions, with anxiety of bourgeoisie life on one end, and the anxiety of solipsism on the other?

parking / part-ing

Two vehicles are parked in the driveway outside the apartment. One is rectangular, broad-shouldered, and tall; the other is thin-waisted and rickshaw-like. Both are made from thin wooden profiles which outline their fragile contours. The male vehicle of the two rests on four rolls of toilet paper, while the rickshaw is passively installed on the floor. The dashboard clock that gives the vehicle an indication of speed and time, was replaced by a domestic alarm clock whose digits are jumbled. The side mirror used for orientation and integration in general traffic was replaced by a round personal makeup mirror. Our movement in the world is measured not only by the forms it spawns, but mainly by accelerations and decelerations, freedoms and limitations. These are the manifestations of our relationship with ourselves and with the outside. What if not these cause the pounding heart, hammering in one’s chest, to accelerate, the hands of time to jumble, the sandstone to break and wear away, and the rabbit to freeze in the car’s headlights?

From this point onward, each will continue her journey separately in the vehicle she built for herself. These cars sample all the mental and social sculptural symptoms characterizing the exhibition into their formal language, and travel on with them. The dependence involved in the “a part from me” relationship is the gateway through which abusiveness, exploitation, and violence enter, but also love, compassion, and intimacy.1

The exhibition is aware of the dual potential inherent in vulnerability, but construes it also as an inevitable space for establishing a relationship. The journey outward does not emerge here as a proposal for salvation, but as an invitation to enter the gates of vulnerability and observe it as a transformative space.

Whether outside the space or within it, Ram and Arad are primarily sculptors, and as such, they build a world and a reality.

So—one more cigarette, pet Alaska the dog, get up from the bench, and move on to the next exhibition.

Read more